Politicians must answer to their constituents, not wealthy special interests. When outside groups can spend unlimited amounts of money on elections, this opens the door to corruption and gives undue power to deep-pocketed interests looking to sway votes.

Thanks to the U.S. Supreme Court’s disastrous decision in Citizens United v. FEC, super PACs are permitted to raise and spend unlimited amounts on elections, including money from corporations and wealthy special interests.

As our elections have gotten dramatically more expensive, candidates have often relied on billionaire megadonors like Elon Musk, who are rewarded with more power over our political system.

During the 2024 election, Musk poured nearly $300 million into super PACs supporting Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, and now that Trump is back in the White House, Musk is being richly rewarded.

Halting this corrupt “pay-to-play" political culture is fundamental to improving the representation of everyday Americans across all levels of government.

One way we can stop this is preventing “coordination” between candidates and super PACs, which are often bankrolled by billionaires and corporations.

Laws prohibiting coordination protect voters by preventing outside groups from spending unlimited amounts on election activity “in consultation or cooperation” with their preferred candidates’ campaigns.

In fact, the Citizens United decision only gave the green light to unlimited special interest spending that is independent from candidates and political parties — not coordinated with them.

The problem is that the laws barring coordination are virtually never enforced; in order to be effective, they need to be strengthened. The Stop Illegal Campaign Coordination Act would outlaw “redboxing” — one of the most common methods of coordination — and help protect our elections.

Redboxing Explained

While super PACs’ election spending is legally required to be independent of candidates’ campaigns, practices like redboxing demonstrate that anti-coordination laws have done little to prevent the close relationship between outside groups and campaigns.

Here’s how redboxing works.

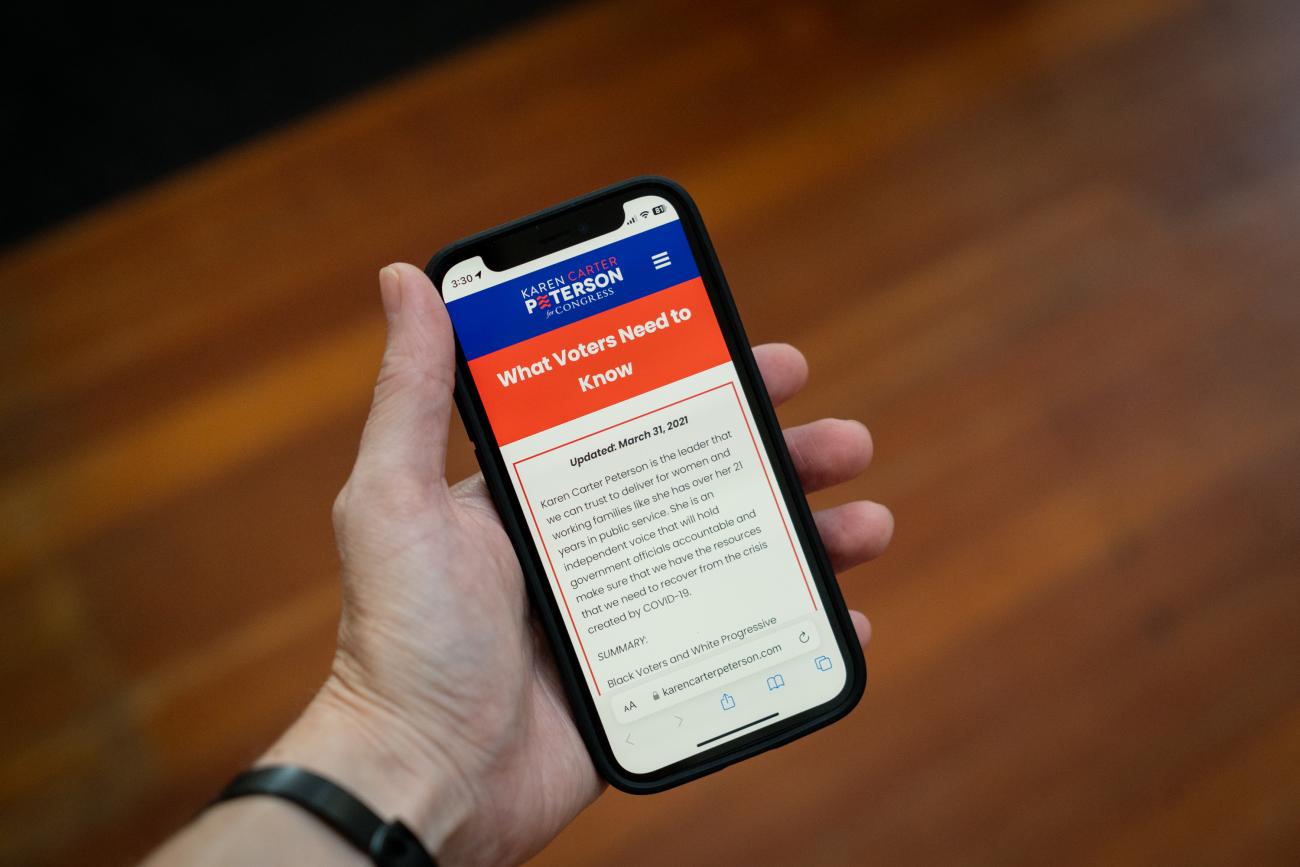

When you visit a federal candidate’s campaign website, you’ll probably find their biography, a story about why they're running, and their positions on important issues. But you also might encounter a bright red box containing this strangely worded phrase: “Voters need to see, read, and see on the go…”

Here is what it looks like:

But this message is not intended for you, a voter — this is a signal to wealthy special interest groups and super PACs.

Known as redboxing, this is an illegal practice where campaigns publish messaging and send instructions to supportive super PACs about what material they should use in their ads, how they should send that material out (e.g., TV ads, digital ads, etc.), and even what categories of voters to target (e.g., suburban women over 40, single men under 35).

A campaign provides messaging on its website and uses widely understood signals (like a literal red box) and specific phrasing (like “voters need to know…”) to direct super PACs to use the campaign’s approved messaging in their ads.

Redboxing also commonly involves posting footage and photos of the candidate, as well as strategy tips about the race. A super PAC supporting the candidate then uses the footage and photos along with the campaign-requested messaging in its ads.

Redboxing on the Rise

Redboxing has become more egregious over time, and the signals have become more sophisticated.

A campaign may use polling data to instruct an allied super PAC to target ads to a specific place and group — e.g., “Voters in St. Louis between the ages of 18 and 35 need to see and see on the go…” — while offering a different instruction for a different place and group — e.g., “Voters in Kansas City over the age of 65 need to read...”

Moreover, redboxing has grown increasingly common: A study of the 2022 election showed that this illegal strategy was used by over 200 federal candidates across the country, frequently resulting in hundreds of times more super PAC spending in those races.

So how do campaigns and super PACs coordinate without facing consequences? As the practice of redboxing demonstrates, the coordination rules are like Swiss cheese: they’re full of holes.

Congress Has the Solution

Coordination, including redboxing, erodes the accountability that everyday voters need from our elected officials.

That is why Campaign Legal Center (CLC) enthusiastically endorses the Stop Illegal Campaign Coordination Act.

Sponsored by Rep. Jill Tokuda (D-HI), this important bill would require the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to assess whether spending by a super PAC or other outside group is “materially consistent” with instructions or guidance from a candidate’s campaign or political party, taking into account whether the campaign or party:

- Suggests specific information about a candidate or party ought to be communicated to voters.

- Offers guidance on which audiences to target with political communications.

- Promotes certain methods of communication to spread information.

- Provides specific message phrasing or multimedia that are subsequently reused by outside political groups.

- Highlights its instructions by setting them apart from other information using a signal or cue.

If a candidate’s campaign or political party has done any of these things, the FEC would have to presume that the outside group’s electoral ads are unlawfully coordinated.

The Stop Illegal Campaign Coordination Act would be a huge step in the right direction, cracking down on tactics used to game our political system and drown out everyday Americans’ voices in our democracy.

To keep up to date with CLC’s fight to improve our campaign finance laws and prevent outside groups from dominating our elections, sign up for our newsletter for the latest updates delivered straight to your inbox.