Although President Trump was elected on a pledge to “drain the swamp” and limit the power of donors and special interests, the money and influence game accelerated rather than slowed in 2017.

Top Trump donors are landing jobs and access. Lobbyists—including foreign government lobbyists—have scored top appointments, and more than half of Trump’s nominees have ties to the industries they are now tasked with regulating. Members of Congress are openly admitting that their work on issues like tax reform was aimed to please donors—or themselves. And we learned this year how Hillary Clinton’s campaign exploited the Supreme Court’s McCutcheon v. FEC decision in disturbing new ways.

With the seemingly endless flow of stories like these, it may have been easy to miss some of the underlying trends in money in politics. Here are three that emerged in 2017 that will likely continue into 2018 and beyond.

1. White House, Dark Money

2017 saw the creation of a multi-million-dollar dark money policy apparatus expressly tied to the White House.

Groups with names like America First Policies openly acknowledge that they are working with the administration while spending millions lobbying for the president’s political and policy interests. Most problematically, they keep their donors hidden from the public.

America First Policies “exists for one reason: to support the president of the United States and his agenda,” according to the group’s president. It was started in January by six of President Trump’s top campaign aides, and its staff have shuffled in and out of the White House ever since. For example, Nick Ayers helped found the group, and is now Pence’s Chief of Staff; Katie Walsh, who was Deputy White House Chief of Staff, left the administration to join the group with the express blessing of senior White House officials.

The Daily Beast found in September that America First Policies planned on spending $12 million in 2017 alone—much more than most dark money groups would usually spend even in an election year. When the tax bill was being debated in Congress, the group launched a website and ran ads like this one, which urged viewers to call Senator Susan Collins to demand she vote for the bill. Once the bill passed, America First Policies celebrated by announcing a $1 million ad buy for a “Thank You, President Trump!” ad set to start airing Christmas Day.

Campaign finance law regulates coordination between candidates and outside groups, but only when those groups spend money on election-related ads. Because America First Policies’ spending is focused on promoting the president’s agenda, campaign finance coordination rules are not implicated.

There is every reason to believe that large donors to these groups give with the understanding that their secret donations are going to be viewed as valuable by the administration. But because donors to these groups remain secret, Congress and the public will never know whether the White House later takes action to advance their interests.

Given the close relationship between these groups and the White House, however, we can expect that the administration knows where the money came from. It is the public who is kept in the dark.

The White House dark money apparatus is new in terms of scope and scale, but it is not entirely without precedent. After the 2012 election, President Obama took the controversial step of creating a 501(c)(4) organization called “Organizing for Action,” prompting criticism from CLC and other reform organizations.

In contrast with the groups that have emerged this year, Obama's 501(c)(4) did take the nominal step of voluntarily disclosing its donors, did not spend significant amounts of money on ads, and ultimately was never a particularly important player. But in forming OFA as a 501(c)(4), Obama set a dangerous precedent that Trump is now exploiting.

America First Policies is not the only group founded by close Trump associates that’s collecting secret donations and using them to support the President’s agenda. Another is Great America Alliance, which proclaimed itself “the largest outside group to support President Trump’s agenda.” (And let’s not forget that this is a spinoff of the PAC that The Telegraph revealed was open to helping foreign donors funnel their money to support Trump’s election via a chain of outside groups.)

The week James Comey testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee, Great America Alliance ran an anti-Comey ad labeling the former FBI Director a “showboat” and “just another DC insider only in it for himself.”

And on October 27th, the group sent an email calling Special Counsel Robert Mueller a “Hillary loyalist” and asking readers to “Join the Alliance today to demand Robert Mueller’s resignation.”

(The same email also proclaimed that, “After almost a year of Trump-Russia conspiracy theories, Mueller’s investigation has yet to file charges, uncover evidence or determine an end date.” The Office of the Special Counsel released the Papadapoulos plea and the Manafort and Gates indictments three days later.)

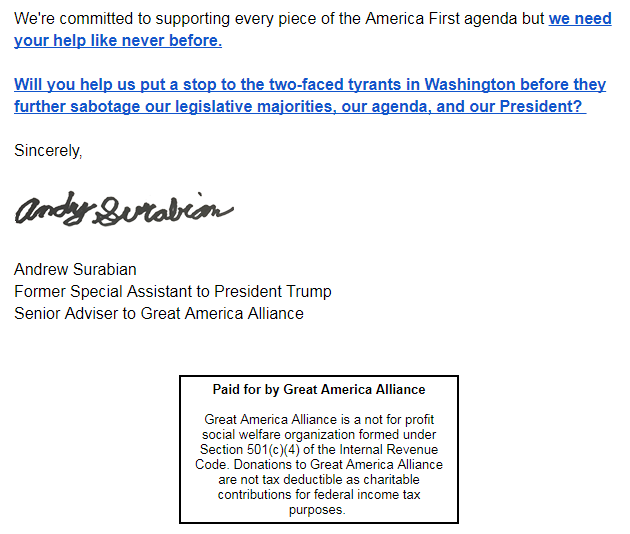

On December 13th, Great America Alliance also implored supporters to “help us stop the two-faced politicians who continue prioritizing their anti-Trump agendas over the will of the people,” assuring them that “We’re committed to supporting every piece of the America First agenda.”

And how was that email signed?

That’s right: “Former Special Assistant to President Trump.” Just to make the connection crystal clear.

2. Donors Give to Super PACs to Curry Influence with Candidates (Duh)

Donors buying influence through super PACs may not be new, but 2017 helped put this reality in a new light.

In Citizens United, the Supreme Court struck down limits on independent expenditures and paved the way for super PACs under the assumption that spending by nominally “independent” groups “undermines the value of an expenditure to the candidate” and “alleviates the danger” that independent spending poses a risk of corrupting candidates.

Part of the logic behind allowing super PACs to raise and spend unlimited amounts is the assumption that donors give to support the PAC’s mission and message, rather than to buy influence with candidates. Since Citizens United, however, we’ve seen a proliferation of super PACS that are staffed by close associates of candidates, receive blessings from the campaigns they support, and spend more than ever; in the 2016 cycle, super PACs spent more than a billion dollars.

The Rebuilding America Now (RAN) super PAC is a good demonstration of the limits of Citizens United’s logic.

In mid-2016, RAN was the super PAC for the Trump campaign. The group was started by two Trump campaign staffers, who launched it just weeks after leaving the campaign (in violation of the FEC’s “cooling off” period, prompting a complaint from Campaign Legal Center). Vice President Mike Pence appeared in one of their fundraising appeals, and told donors that “Supporting Rebuild America Now is one of the best ways to stop Hillary Clinton and help elect Donald Trump our next president!"

Many of those big donors saw their investments pay off. The private prison giant GEO Group gave RAN $225,000 through a subsidiary, and in 2017 saw the Trump administration reverse an Obama-era policy phasing-out private prisons. The Trump administration also granted GEO a multimillion dollar government contract for new facilities, like this one planned for Texas. RAN also got $450,000 from the mining industry, and saw its investments pay off in the form of slashed regulations, as the Center for Responsive Politics observed. Linda McMahon gave $6 million to RAN in 2016, and became President Trump’s pick to lead the Small Business Administration.

However, once RAN itself found itself on the outside of Trump’s inner circle, the donations dried up. It turns out that donors didn’t give to RAN because they loved its mission and its message; they gave because of its perceived proximity to Trump.

The two men who launched RAN, Laurance Gay and Ken McKay, were associates of Paul Manafort. When Manafort was Trump’s campaign manager, he brought the two onto the campaign, and blessed their formation of the super PAC.

RAN dialed-down its fundraising projections when Manafort was booted from the campaign, but still raised funds at a healthy clip, perhaps because Manafort and Trump still maintained regular contact. Manafort’s connection to Trump effectively ended as the Russia probe heated up—and with it, RAN’s ability to claim any sort of connection to Trumpworld.

And once it was clear that RAN no longer had ties to the president, donors no longer had any interest in supporting the group.

3) Political Operatives Find New Ways to Keep Voters in the Dark

Finally, this year’s special elections brought with them not only unprecedented levels of spending but also new dark money schemes to hide the origins of election spending from voters

In Bloomberg BNA’s analysis of independent expenditures in the Georgia, Montana, and South Carolina special elections, almost half of spending in those elections came from undisclosed money—through non-profits, trade associations, or super PACs that received donations from dark money groups.

A major source of that secretive spending arose from groups that don’t disclose their donors making pass-through contributions to entities that do, like super PACs. In the Georgia special election, the dark money group American Action Network gave $5 million to the Congressional Leadership Fund super PAC, which spent $7.5 million in support of the Republican candidate Karen Handel.

While the Congressional Leadership Fund technically complied with current reporting requirements by reporting American Action Network donations, the vast majority of its underlying donors remain a mystery.

Most recently, in Alabama, we saw another creative dark money scheme. Supporters of then-candidate Doug Jones formed a super PAC called Highway 31—but it wasn’t just any super PAC. Rather, the race’s biggest independent spender financed its $5 million in spending with debt and thus avoided reporting any donors to the FEC before election day, as the Daily Beast reported. Days before voters went to the polls, Politico reported that Highway 31 was a joint project of the two largest national Democratic super PACs, Priorities USA and Senate Majority PAC.

We can expect to see this scheme repeated in future elections, depriving voters of information about who is trying to influence their vote until well after election day.

As we head into another election year, we’ll need to keep a vigilant eye on all of these threats—and keep the pressure on the FEC and Congress to rein them in.