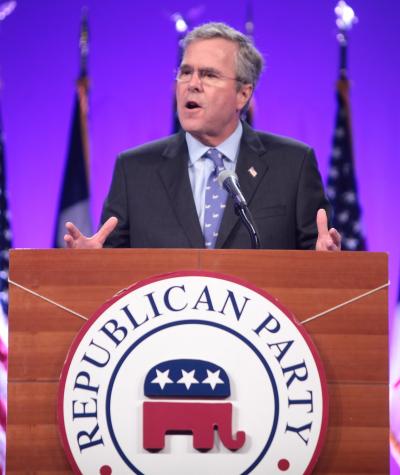

In the 2016 presidential primary, Jeb Bush postponed officially declaring himself a candidate for months while he formed, staffed, operated, and fundraised for a major super PAC that would go on to spend millions of dollars to promote his presidential run.

Now, more than five years after the activity began, this scheme still stands unaddressed by the Federal Election Commission (FEC). The case is a particularly striking display of our broken campaign finance system—and of persistent dysfunction at the FEC, which has yet to take any action in response to the complaints Campaign Legal Center (CLC) and Democracy 21 filed on the matter in mid-2015.

For months before registering his candidacy, Bush headlined $100,000-per-ticket fundraisers for the super political action committee (PAC)—named Right to Rise—in cities across the country. His family helped solicit contributions. Bush and his close advisers staffed and constructed strategy for the super PAC, including a plan for how it would most effectively complement the campaign’s efforts.

He traveled to early primary states, met with potential donors and staff, and publicly acknowledged that he was running for president.

In 2015, as the evidence accumulated, CLC and Democracy 21 filed two complaints with the FEC alleging that Bush violated the law by failing to register and report as a candidate, and that Bush and Right to Rise illegally outsourced campaign operations to Right to Rise, a super PAC set up, operated, and financed by Bush and his close aides.

When you become a candidate, you must register with the FEC and begin filing regular reports that disclose how much you’re spending and raising. You also must operate within certain constraints that guard against corruption, like contribution limits and source restriction that prohibit direct donations from corporations and unions.

Yet Bush, despite taking action as a candidate for months, failed to declare his official candidacy until mid-June 2015—five months after he and his aides formed the super PAC, and months deep into his cross-country fundraising blitz.

By the time Bush did finally declare he was a candidate, he had stockpiled about $90 million for Right to Rise, which unlike his campaign could raise unlimited contributions from individuals and corporations. It would go on to report spending tens of millions of dollars advocating Bush’s election in the Republican presidential primary.

More than five years later, the FEC has not resolved this matter. So, this spring, we sued.

The law allows anyone who has filed a complaint with the FEC to file suit in federal court if the agency has not acted after 120 days. Long delays have become common at the FEC; CLC alone has more than 40 complaints that have been pending for more than 120 days. Yet, even by recent FEC standards, this delay is remarkable: the 120-day window has elapsed more than fifteen times over.

After we sued, the FEC defaulted, meaning that it could not even muster the four votes it needed to appear in our lawsuit. (From August 2019 until the beginning of June 2020, the FEC had only three members, but it had regained a fourth in time for it to authorize a defense to our suit. It did not.)

That might have been the end of it. Instead, one of the administrative respondents, Right to Rise super PAC, intervened to defend the delay even though the FEC itself would not. In intervening, the super PAC openly admitted its strategy, at least in part, was to run out the clock so it can’t be penalized for its violations of campaign finance law.

That clock indeed is ticking—at least on the imposition of monetary penalties—and it underscores one of the many problems arising from the FEC’s extraordinary delay.

The indefinite limbo also means that we know no more today about where this matter stands than we did when we first filed our complaints over five years ago. We are even in the dark about what stage in the process the FEC has reached—because only after an FEC complaint is fully resolved is the case file made public.

The disclosure of that file is crucial for a number of reasons: it helps campaign finance watchdogs like CLC fully understand and inform the public about enforcement matters, it brings to light facts that may have been uncovered in the course of an investigation, it reveals the how the FEC is interpreting and applying federal law to the alleged facts, and it provides either a red or green-light to present-day candidates and committees that may be considering engaging in similar activity.

What’s more, if the FEC ultimately finds that a legal violation occurred, the violators will have to at the least provide overdue campaign disclosure so the public can learn the answers to a host of otherwise-outstanding questions.

That would include knowing when Bush crossed the legal threshold of candidacy, where his early money came from, and how much of this money he spent—and on what—in the first half of 2015. Equally importantly, voters would learn exactly how the relationship between Right to Rise and the Bush campaign operated, and what sorts of in-kind contributions may have flowed from the PAC to the candidate.

Because of the FEC’s five-year delay, we know none of this.

Meanwhile, super PACs have continued pouring money into elections across the country, and instances of candidates working closely with those supposedly independent groups have further proliferated. Since 2016, super PACs have spent over $1 billion more in federal elections, and super PACs that support only a single candidate—as Right to Rise did—have accounted for over $245 million.

The FEC is the only government agency entrusted with enforcing and administering the federal campaign finance laws. When it delays for years in resolving enforcement matters, the voting public is indefinitely—and improperly—left in the dark.

Voters have a right to know which wealthy special interests are spending big money to secretly influence our vote and our government to rig the political system in their favor.