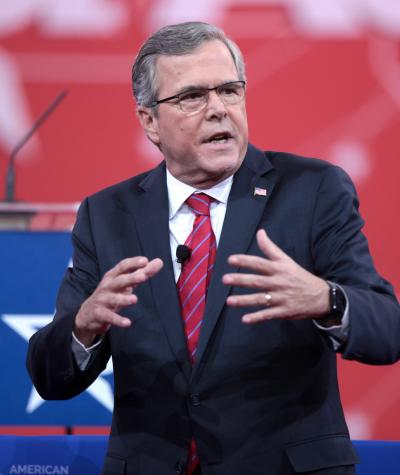

Last week, the Federal Election Commission (FEC) levied $940,000 in record-breaking fines after a Chinese-owned corporation illegally gave $1.3 million to Right to Rise, the super PAC that supported Jeb Bush in the 2016 election.

Such fines are rare. But illegal foreign funds in elections likely are not. They are just rarely identified.

The illegal $1.3 million contribution came from American Pacific International Capital (“APIC”), a corporation formed in California but wholly owned by two Chinese citizens. APIC’s five-member board included two U.S. citizens, including Jeb Bush’s brother Neil.

Despite APIC being wholly owned and controlled by Chinese nationals, current law allows a corporation like APIC to give legally to super PACs, as long as U.S. nationals direct the contributions.

What made APIC’s contribution illegal is that its president Gordon Tang, a Chinese national, approved it. Tang admitted in an interview with The Intercept – on tape! – that he directed the contribution. Right to Rise was also on the hook because Neil Bush was an agent of the super PAC, and an FEC investigation showed that he asked Tang to make the contributions.

Absent The Intercept’s reporting, and absent these on-the record statements from APIC officials, the FEC would likely never have opened an investigation into APIC.

Foreign-owned corporations can readily get around the ban on foreign money by being just a little bit careful (and not, for example, admitting to reporters that they violated the law). Even if a corporation’s foreign owners refrain from directing their firm’s contributions, in practice this means little, since any U.S. national working for the firm likely knows which candidates the foreign owners want to support.

There is every reason to suspect that this is not an isolated incident. Foreign nationals have a demonstrated interest in influencing U.S. elections, and corporations offer an easy way to do so without detection.

APIC’s contribution was identified because it was made to a super PAC and publicly disclosed – allowing The Intercept reporters to dig deeper. Any foreign-owned or foreign-controlled corporations that secretly gave to dark money groups, in contrast, are not known.

Dark money nonprofits have reported over $1 billion in political spending to the FEC, but because their donors aren’t reported, we can’t know how much of that money came from foreign sources. The NRA’s nonprofit arm, for example, spent over $33 million on the 2016 elections, and prosecutors are reportedly investigating whether any of those funds came from Russia. We also don’t know the extent to which foreign actors have used shell corporations like LLCs as pass-throughs to make anonymous contributions; there is some evidence that foreign nationals funded Trump’s inaugural committee through pop-up LLCs.

This is a problem of Citizens United’s making. That Supreme Court decision opened the door to corporate political spending and paved the way for super PACs and dark money groups.

Citizens United didn’t touch the ban on foreign political spending – it just made it easier to evade.

The $900,000 in fines levied against APIC and Right to Rise are the largest the FEC has levied since Citizens United, and the third-highest in FEC history. But rather than being an example of the system working, this investigation hints at how broken the system really is – and how vulnerable it remains to foreign interference.

Several bills have been introduced to strengthen the ban on foreign money in elections. The DISCLOSURE Act and REFUSE Act include provisions defining a corporation as a “foreign national” subject to the law’s contribution ban if it is more than 20 percent owned by foreign nationals. If such a provision had been law in 2016, APIC would have been prohibited from giving to a super PAC in the first place – it wouldn’t have taken a lengthy investigation and three years to establish that the contribution was illegal. Legislation like HR 1, the "For the People Act," would also require politically-active dark money groups to disclose donors, closing down an avenue by which foreign funds can be laundered into U.S. elections without detection.

The loopholes exploited by foreign actors in the 2016 elections are certain to be used again in 2020 and beyond – unless Congress takes action.