Updated: Oct. 13, 2020

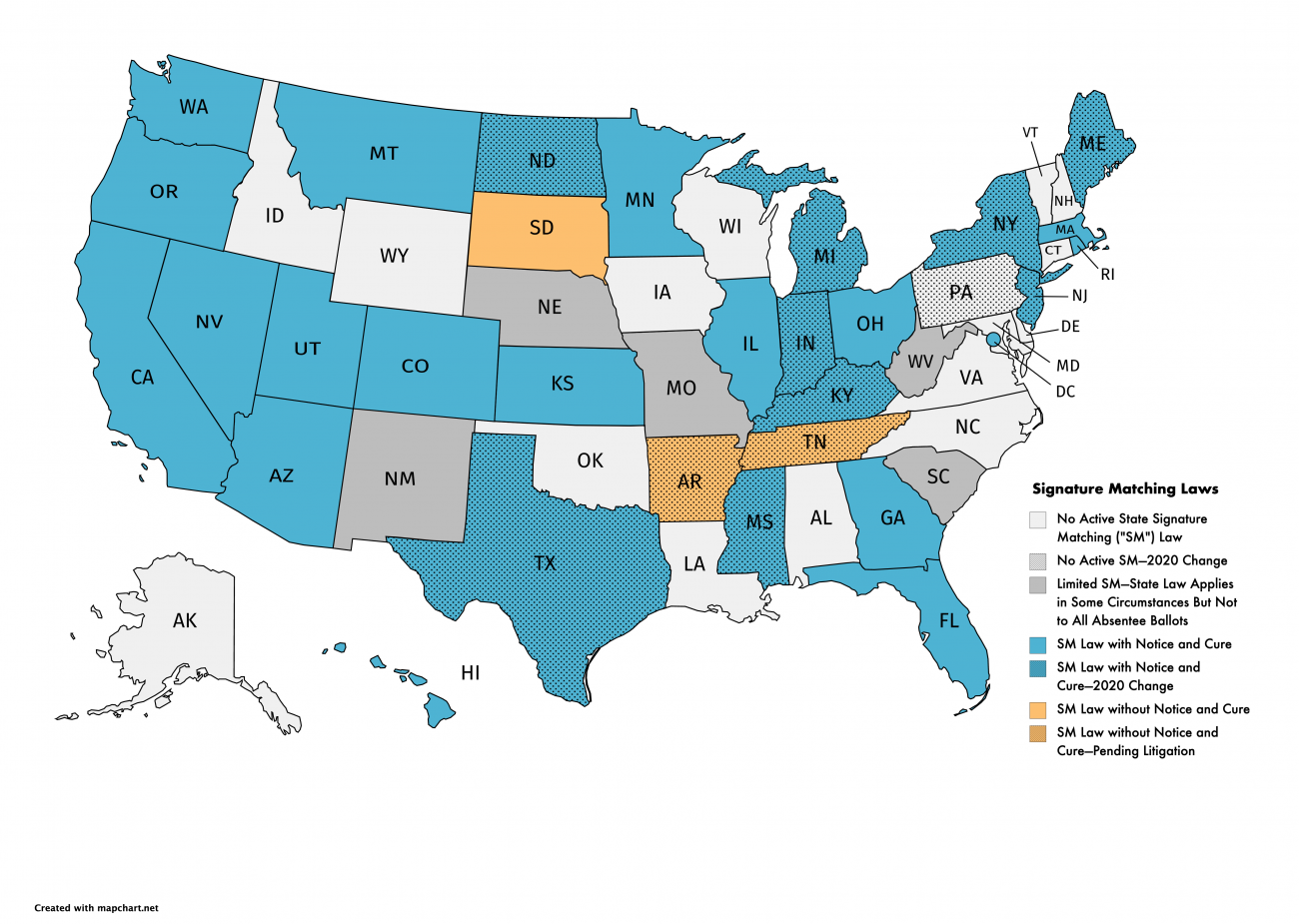

Many states rely on signature matching as part of ballot counting and verification procedures. Indeed, at least 31 states will use signature matching to verify all mail ballots in the upcoming November 2020 election.

Signature matching laws require election officials to compare the signatures voters provide on their ballots to the signatures on their voter registration or mail-in ballot request forms. If election officials determine the signatures do not match, the ballot is rejected and not counted.

Signature evaluation is notoriously unreliable and error-prone. It can result in ballot rejections based on nothing more than poor penmanship. Thus, when a state relies on signature matching to verify mail ballots, it must provide voters notice of signature problems, and a meaningful opportunity to verify their identity and ensure their votes are counted.

These “notice and cure” policies are mandated by the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Many States Provide Notice and an Opportunity to Cure

To our knowledge, at least 31 states have active signature matching laws (or interpret their signature verification laws to require signature matching) for vote-by-mail ballot verification. Of those states, 25 provide voters notice and opportunity to verify their identity when there are signature discrepancies.

Nine states—including Maine, North Dakota, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania—created notice and cure policies in 2020 after lawsuits or advocacy by the Campaign Legal Center (CLC) and allied organizations. Four states—Tennessee, Mississippi, Arkansas, South Dakota—still do not have any notice and cure policy; all but South Dakota are now in pending litigation.

Robust Notice and Cure Policies Reduce Ballot Rejection

As record numbers of voters rely on mail voting amid the COVID-19 pandemic, states must assure voters that their ballots will not be tossed aside because of problems that can be easily fixed before the election concludes. Indeed, when states make a reasonable effort to contact voters about signature discrepancies and verify their identity, voters are eager to ensure their votes will be counted.

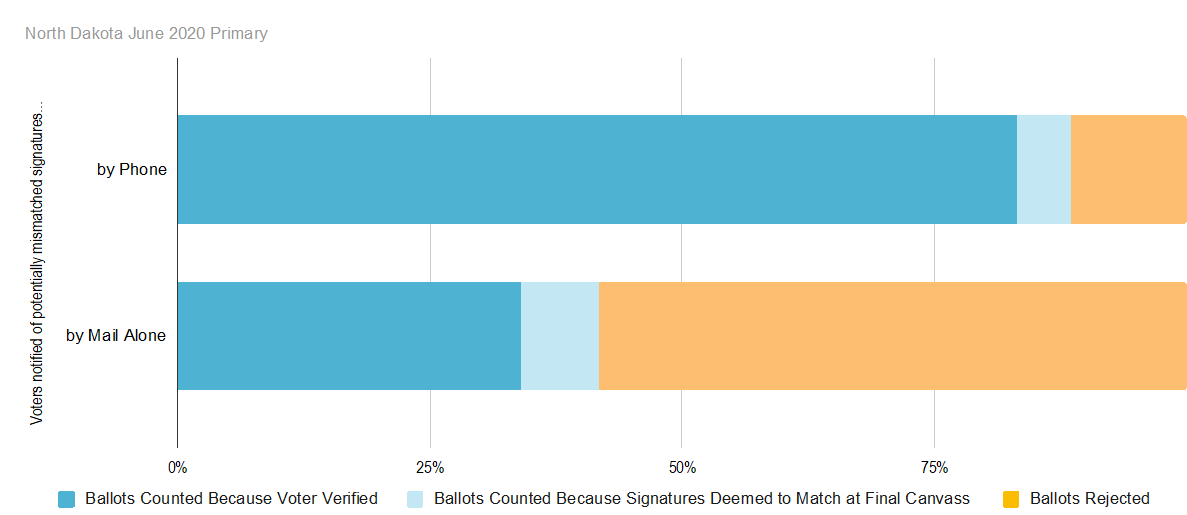

Consider, for example, North Dakota. After CLC sued, a federal court ordered the state to implement robust notice and cure policies for the first time in its June 2020 all-mail primary. Election officials had to contact voters by mail and phone if a number was on file about signature issues. Voters could then verify their identity by phone, mail, or in person within six days of Election Day.

In that election, over 58% of ballots flagged for mismatched signatures were counted because the voter verified their identity. And even though the number of vote-by-mail ballots increased dramatically from 2018 to 2020, the number rejections for mismatched signatures decreased by 20% after the court-imposed notice and cure process.

How to Design Notice and Cure Policies That Minimize Ballot Rejection and Ensure That Every Vote Counts

Some notice and cure policies protect against erroneous rejection better than others. The most effective policies share two important features:

1. Notice and Cure by Phone. The most efficient and effective way to notify voters about signatures issues is by phone—not mail. In a quick call, a voter can verify their identity and have their vote counted. Mail can be delayed, especially near Election Day, making it difficult to fix issues before the election concludes. In the North Dakota’s June 2020 primary, as shown below, 83% of voters notified by phone were able to verify their ballot in time to be counted as compared to only 34% of voters notified by mail alone. States must make every effort to contact voters by mail and phone where possible, and permit voters to verify their ballot with any oral or written response.

2. Sufficient Time to Cure. Voters must have time to fix ballot problems before election results are finalized. States should create sufficient time in two ways: (i) allowing election officials to begin processing and verifying mail ballots as they are received or at least five days before Election Day, and (ii) permitting voters to fix ballot issues for a maximum possible time after Election Day.

Questions? Contact Campaign Legal Center (CLC) at [email protected].