For the first time, the State of Maine joins numerous municipal jurisdictions across the U.S. in using ranked choice voting all of its primary and general elections.

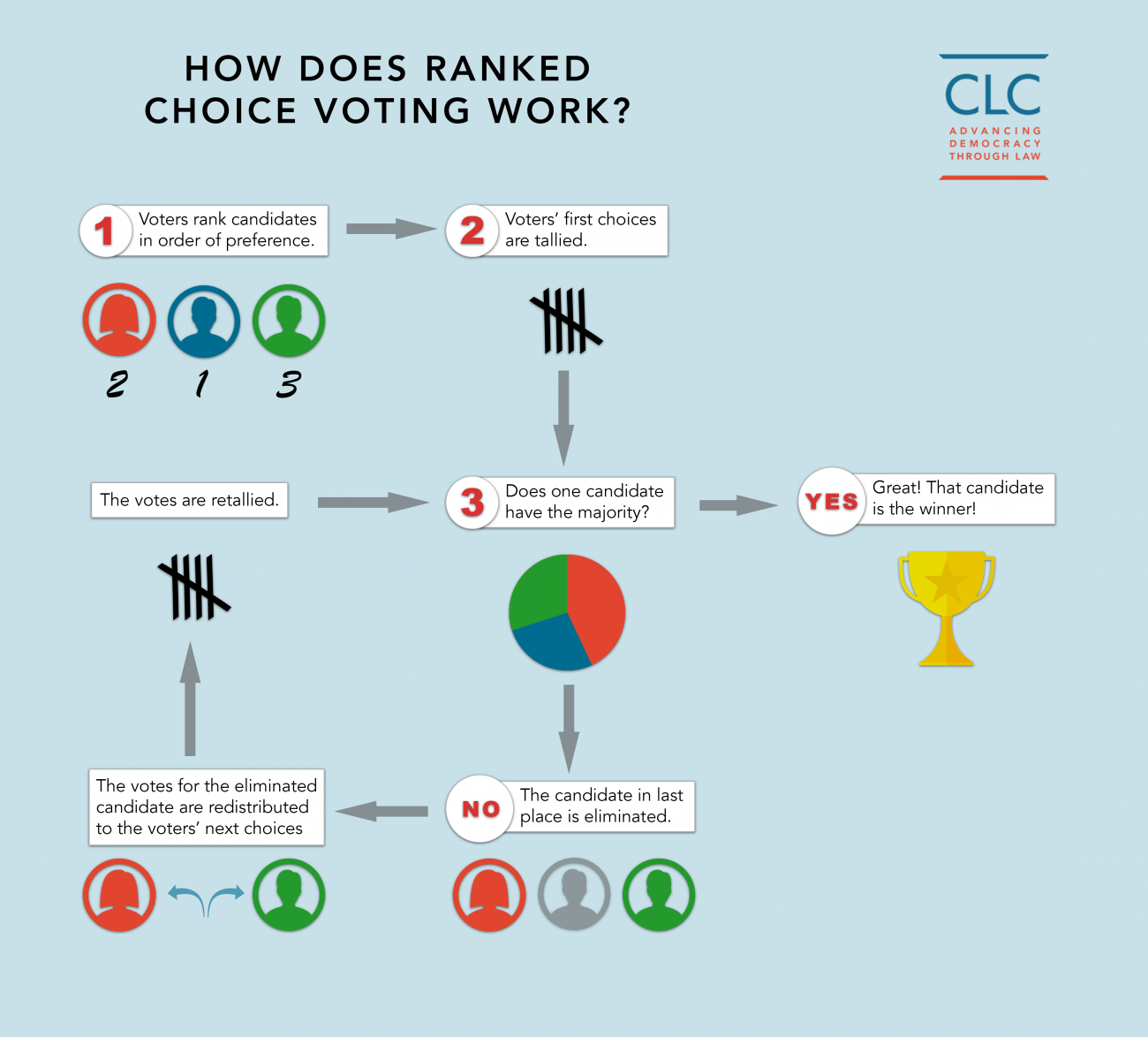

Ranked choice voting (RCV), also known as instant runoff voting, asks voters to rank the candidates for an office in order of preference; then, when results are tallied, the votes for the candidate with the lowest first vote total are reassigned to the next-highest-ranked candidate on each voter’s ballot—so long as that candidate remains in the running.

This process repeats itself with the candidate who has the lowest number of votes after reassignment until one candidate has a majority and is declared the winner.

Elections for public office aren’t the only context in which ranked choice voting can be an effective method of choosing a winner from among a group of nominees.

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (the “Academy”) has employed ranked choice voting to determine the winner of the Best Picture Oscar since 2009, when they expanded the number of nominees from 5 to 10.

That includes this past weekend’s Academy Awards, where the South Korean film “Parasite” became the latest Best Picture winner (and the first non-English-language film in the Academy’s 92-year history) to triumph under this system.

In a way, recent Best Picture races have been similar to the current Democratic presidential primary contest and the Republican primary of 2016—both of which featured a large number of candidates with varying levels of support, and although there may have been a frontrunner or favorite, neither of those two electoral contests featured a candidate with the support of a majority of voters—at least initially.

(It’s challenging to make a one-for-one comparison between the Academy and any election for public office, because the Academy does not release the results of voting for either the Oscar nominees or the winners. But we can make reasonable assumptions based on published Academy rules and outcomes as we can observe them.)

Just like in many primary campaigns, Academy voters have to choose from among a large number of candidates for Best Picture.

Moreover, because each Best Picture nominee needs to pass at least a 5% threshold of first place votes to even be nominated, first ballot support is necessarily spread across the nominees, and it’s unlikely that any one film will command a majority of votes on the first ballot.

Faced with such a broad array of choices, it is easy to imagine a scenario in which no single candidate or nominee wins a majority of votes, which means that most voters won’t get their first choice.

Using RCV allows those same voters to reassign their votes to their second or third choice candidate, increasing the likelihood that the winning candidate is broadly acceptable to a majority of the electorate. RCV is an improvement on existing electoral procedures because it incorporates the best elements of other electoral systems.

Like the Iowa caucus process, it prevents voters from “wasting” their votes on candidates that are unlikely to (or in some cases, certain not to) advance to the next stage; but unlike a caucus, RCV occurs instantaneously at the counting stage and doesn’t require voters to spend hours at a caucus site physically realigning themselves, and the ballots with preferential voting orders on them can provide a paper trail for easy recounting or recanvassing.

Using RCV rather than a caucus also allows for absentee voting and lessens the burden on voters with young children, disabilities or work schedules that make participating in a caucus especially challenging, if not impossible.

RCV also ensures that the ultimate victor will be broadly acceptable to the highest number of voters by requiring a candidate to receive at least some support from a majority of voters.

In that way, it’s similar to elections in places like Georgia, which require a runoff between the top two vote-getters if no candidate gets more than 50% of votes in the first instance. Unlike with a standard runoff, however, RCV doesn’t require voters to cast ballots a second time—their second choice has already been accounted for, and the runoff takes place instantaneously.

This is not only more convenient for voters, who don’t have to make arrangements to get to the polling place or remember to send an absentee ballot a second time; it also lessens the burden on election administrators, who would no longer have to mobilize their staffs and expend resources to conduct an entire second election.

RCV has numerous other benefits, including an increased likelihood that minority communities of interest and third party supporters can maximize their chances of electing their candidates of choice, providing more choice for voters and minimizing vote splitting, and discouraging negative campaigning and limiting political polarization.

In any event, the Academy has shown that ranked choice voting can be easily implemented in ways that are both accessible to those voting in an election and administrable by those running it—envelope fiascos notwithstanding.

Although the results may have been mixed from a critical standpoint from year-to-year, the Academy’s RCV system has resulted in some of the most uniformly acclaimed Best Picture winners of all time, many of which were also historical milestones, such as “The Hurt Locker,” “Twelve Years a Slave,” “Moonlight,” and this year’s “Parasite.”

But RCV is not about achieving a particular outcome; rather, it’s about establishing a process that most accurately reflects the will of the majority of voters—whatever that will might be.

Watch our video on RCV.