In a letter to Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, the Judicial Conference quietly shared a decision that will significantly hamper ethics enforcement across the federal judiciary.

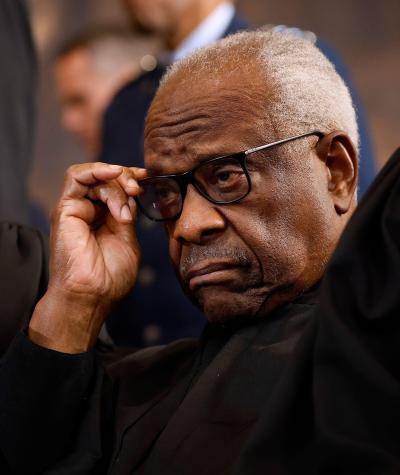

The Judicial Conference, which is charged with enforcing the financial disclosure law for the federal judiciary, was asked to determine whether there was evidence to support allegations that Justice Clarence Thomas engaged in a 30-year pattern of intentionally filing false financial disclosure reports.

Instead of answering “yes” or “no” for this one matter, the Judicial Conference effectively eliminated the rule prohibiting all judges and justices from filing false reports.

The Ethics in Government Act (EIGA) prohibits the filing of false reports and is intended to penalize anyone who intentionally attempts to hide information from the public related to potential conflicts of interest.

The Judicial Conference indicated in its decision that if a justice or judge amends a financial disclosure report after there are allegations that it was false, there is no longer a need to question whether the original report was an intentional violation of law.

Allowing someone to avoid any penalties by filing an amendment, even if they intentionally hid the information, makes the EIGA meaningless. This interpretation is in direct opposition to how the other branches have interpreted the EIGA and the prohibition on filing false financial disclosures.

Congress, for example, has stated for nearly 40 years that the need to enforce the law by identifying missing information in financial disclosure statements can clash with the need to accept “amendments to such statements that may well have been intended to have a mitigating or even exculpating effect.”

Consequently, members of Congress are only given the benefit of the doubt if they file an amendment very shortly after the original report unlike the blanket exemption for amendments that the Judicial Conference decision could create.

The Judicial Conference’s bizarre conclusion only reinforces that the U.S. Supreme Court needs an independent ethics enforcement body, something Campaign Legal Center (CLC) has called for many times over the past few years.

Even more consequential is the Judicial Conference’s conclusion that “[t]here is reason to doubt that the Conference has any such authority [to refer a Justice to the Attorney General].”

This is contrary to the plain language of the EIGA, which states that the Judicial Conference “shall refer to the Attorney General the name of any individual which such official or committee has reasonable cause to believe has willfully failed to file a report or has willfully falsified or willfully failed to file information required to be reported.”

The Judicial Conference accepts their role to oversee whether or not justices comply with the EIGA, but it narrowly reads the requirement for it to “notify the judicial council of the circuit in which the named individual serves of the referral.”

And because a Supreme Court justice is not within a circuit, they leaped to a counterintuitive result that justices may be exempt from referrals to the attorney general.

Under the Judicial Conference’s interpretation, the few parts of the judiciary that are not under a circuit (e.g., U.S. Sentencing Commission, Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, Supreme Court), are functionally exempt from a referral to the attorney general, even if there is evidence that such a person clearly engaged in criminal conduct and violated the disclosure rules.

With this reasoning, the Judicial Conference argues that they have no responsibility to refer a Supreme Court justice to the attorney general when they violate ethics standards — setting a dangerous precedent where our government cannot enforce laws against the members of our highest court.

This decision creates strange exceptions to the law contrary to the law’s original purpose. When President Jimmy Carter signed the EIGA into law in 1978, it was intended to be an enforceable law, not just a list of disclosure requirements.

The Judicial Conference’s decision comes at a time where the federal judiciary is already facing historic low levels of public trust. By abdicating its responsibility to enforce the EIGA with regards to Justice Thomas, the Judicial Conference paves the way for Supreme Court justices to continue flouting ethics standards and erode American’s belief in the institution.

One way for the federal courts to improve their standing is to show that they take ethics enforcement seriously by creating an independent ethics body to uphold the laws and restore public trust.

A system of self-policing ethics is rarely effective, in part because of the appearance of conflicts of interests when the enforcement body may be concerned with retaliation or other negative consequences.

This may very well be the reality for members of the Judicial Conference, who could fear judgment and criticisms from their colleagues for any decisions they make that bring accountability to the courts.

Bringing true accountability to the federal judiciary — including the Supreme Court — requires a truly independent enforcement mechanism comprised of decision makers outside of the court system.

CLC supports an independent enforcement mechanism as one of the key approaches to improving ethics standards at the Supreme Court. For more information on how to approach this essential mission, visit our action page.