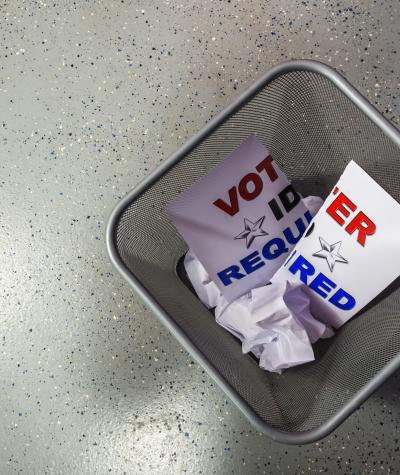

On Monday February 27, the Department of Justice began its official retreat from protection of minority voting rights by filing a motion to dismiss its intentional discrimination claim against the state of Texas for its strict voter identification law (“SB 14”). Both because this move represents the Department’s first official position on voting rights issues and because the Texas voter ID litigation has stood at the center of the recent firestorm over state discriminatory encroachments on the right to vote, this move is notable even if unsurprising.

SB 14, the nation’s strictest voter ID law, was expertly crafted to burden minority voters. It sought to limit voters’ ability to prove their identity to seven documents: a Texas DPS-issued driver’s license, personal ID, or election identification certificate; a U.S. passport; a U.S. military ID; a citizenship certificate with photo; or a concealed weapon license. In so constructing SB 14, Texas excluded many forms of ID typically accepted by other states with photo ID laws, including public university student and employment IDs, federal employment IDs, and Texas state employment IDs. All of these excluded IDs are disproportionately held by minority voters in Texas. Meanwhile, the Texas legislature went out of its way to include a concealed weapon license on the limited list of acceptable IDs—an ID primarily held by Anglo voters. The result of these and other choices was a law that threatened to disenfranchise over a half a million voters. The evidence demonstrated that over 600,000 registered Texas voters, disproportionately black and Latino, did not have the required SB 14 ID.

This was not an accident. SB 14 was passed in 2011 at a time when the Legislature was increasingly aware of a growing minority population poised to increase its political power in the state; a change that would have undeniably detrimental effects to the ruling Republican party, given the racial polarization along party lines in Texas. Indeed, on March 10, a three-judge federal court issued over 400-pages of findings of fact concluding that the same Texas Legislature that passed SB 14 also intentionally discriminated against minority voters in its redistricting plan. Texas legislators were warned of SB 14’s likely impact on minority voters yet repeatedly rejected ameliorative amendments that would ease its burden. Later, during the litigation, those legislators were unable to explain why the amendments were unacceptable.

From 2012 until last month, the Department of Justice took the position that SB 14 was passed with discriminatory intent. It first did so after carefully reviewing the facts provided by Texas in its suit for pre-clearance before a three-judge federal court in the District of Columbia. Texas lost that case because the court unanimously held that Texas could not show that the law would not have a retrogressive effect on minority voters. But when the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act in Shelby County v. Holder (2013)—largely eliminating pre-clearance by striking down the coverage formula for the pre-clearance requirement—the Texas Attorney General announced the same day that it would go forward with enforcing SB 14. The Department of Justice joined private plaintiffs in suing Texas to stop enforcement of SB 14 under the remaining section of the VRA, Section 2, once again alleging that the law was passed with discriminatory intent.

The District Court in that case agreed with the Department of Justice. After years of dilatory appeals, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, sitting en banc, decided 9-6 that not only does SB 14 have an unlawful discriminatory result under Section 2 but also that there was sufficient evidence to support a finding of intent (although it quibbled with some of the District Court’s reasoning and sent the intent inquiry back to the District Court for further findings). The Fifth Circuit is largely considered one of the most conservative courts in the nation and yet it found (by a not inconsiderable margin) that the intent claims had significant evidentiary support worthy of pursuit: “[T]here remains evidence to support a finding that the cloak of ballot integrity could be hiding a more invidious purpose.” In November and December of 2016, the Department of Justice submitted over one hundred pages of proposed findings of fact as well as voluminous briefing supporting its position that SB 14 is infected with a discriminatory purpose.

Yet from day one of this Administration, it appeared that the Department was prepared to make an about face. Just hours after inauguration, the Department filed a motion to continue the scheduled January 24 hearing to allow the Department time to “brief” the new administration. As the new hearing date approached, the Department then filed a joint motion—with the State of Texas and opposed by the private plaintiffs—asking the court to once again continue the matter because amendments to SB 14 in a new bill, SB 5, had been introduced in the Texas Legislature. When that motion was denied, the Department cited the court’s denial as its reason for seeking dismissal of the intent claim.

The Department’s stated reason for dismissing its intentional discrimination claims merits little credibility. The Texas Legislature asked the Court for a continuance last August, based on exactly the same premise arguing that the hearing should be delayed until the Legislature could take up amendments in the next session. At that time, the Department opposed such delay, arguing that it was “in the interest of justice” to resolve the intent issue as soon as practicable. The Department was right then and the Court was right both then and now in denying the continuance.

Any amendments to SB 14—even if they pass and even if they remedy some of the law’s racially discriminatory results—are irrelevant to the question of whether SB 14 was passed with a discriminatory purpose in 2011. This is a legal issue that must be resolved first, even if the SB 5’s passage could affect the scope of the remedy. That is because a finding of discriminatory intent has independent legal significance that could lead to additional remedies under Section 3(c) of the Voting Rights Act.

Further, the conclusion that SB 14 was enacted with discriminatory intent would also affect analysis of whether the Legislature’s amendments resolve the law’s constitutional deficiencies. While a finding of discriminatory results would require a more limited remedy, a finding of discriminatory intent means that the law has no legitimacy whatsoever. In that circumstance, an amendment that merely builds on the basic discriminatory structure of SB 14—as SB 5 does—would likely be insufficient to save the law. (The three-judge court opinion in the Texas redistricting case provides further explanation of why this type of subsequent amendment does not moot an intent case.)

Thus, Texas’s belated introduction of SB 5, and the Department and Texas’s joint pleas for delay, are nothing more than an attempt to avoid an intent finding that could prove more difficult to overcome in establishing a new (slightly less) discriminatory voter ID scheme. In that way, it is reminiscent of the type of whack-a-mole legislation that created the need for Section 5 pre-clearance in the first place.

As a practical matter, the Department’s move will have relatively little effect on the litigation, at least in the short term. There are private plaintiffs in the case represented by CLC and several other private civil rights organizations and litigators.

But it is notable that the Department did not remove itself entirely from the litigation. Rather, it declined to dismiss its claim that SB 14 has racially discriminatory results. This was a strategic move, which allows the Department to argue that it is taking a balanced and nuanced step without actually requiring it take an adversarial stance against Texas. After all, the discriminatory results claim is already fully resolved. The district court’s finding of discriminatory results was affirmed by the Fifth Circuit’s en banc opinion, and the Supreme Court then denied Texas’s petition for certiorari on the issue. If anything, the Department may have kept its discriminatory results claim only to further undermine the case: it is possible the Department could do more harm during the remedy phase by readily agreeing with Texas that whatever remedy the State proposes is sufficient.

As a first indication of voting rights under the Trump administration, the Department’s decision to reverse course on its claim of intentional discrimination forebodes an abandonment of the project of federal oversight of discrimination in voting. The Texas voter ID litigation is at the center of the story about voter suppression in the wake of Shelby County. It is the strictest and arguably most discriminatory voter ID law in the nation. Moreover, despite findings of discrimination from no fewer than thirteen federal judges in four separate opinions, the lack of a pre-clearance requirement meant it was enforced in the interim from 2013 until November 2016. And Texas now seeks to evade a finding of intent by amending its law at the eleventh hour, a move that I’m sure is startlingly familiar to anyone who can remember litigating voting rights before pre-clearance protections. Remarkably, the Department of Justice, charged with enforcing the Voting Rights Act against the states, has aligned itself with the state in this litigation.

This shift raises larger questions about our legal structure for enforcing federal guarantees of non-discrimination. The Voting Rights Act and other anti-discrimination laws were passed with the purpose of overriding state prerogatives when they interfere with the guarantees of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. In leaving the primary enforcement of those laws to the Department of Justice, these federal anti-discrimination statutes assumed that the federal government was a trustworthy protector of those guarantees. Yet, the current Attorney General appears to object to federal interference in local affairs, even when discrimination is at issue. He has expressed skepticism of the Department’s investigation of police discrimination—saying it is a “difficult thing” for a police department to be sued by the Department—and has described the Voting Rights Act as “intrusive.”

I imagine Attorney General Sessions is likely to empathize with Judge Gerry Smith’s view of the Department’s prior litigation against discriminatory voting measures, as expressed in Smith’s dissent in the Texas redistricting case:

"It was obvious, from the start, that the DOJ attorneys viewed state officials and the legislative majority and their staffs as a bunch of backwoods hayseed bigots who bemoan the abolition of the poll tax and pine for the days of literacy tests and lynchings. And the DOJ lawyers saw themselves as an expeditionary landing party arriving here, just in time, to rescue the state from oppression, obviously presuming that plaintiffs’ counsel were not up to the task. The Department of Justice moreover views Texas redistricting litigation as the potential grand prize and lusts for the day when it can reimpose preclearance via Section 3(c)."

Putting aside the colorful language, Judge Smith’s dissent expresses a disdain for the entire enterprise of a federal entity that “lusts” for the power to police state voting regulations to ensure non-discrimination. But that was exactly the design of the Voting Rights Act.

What we are seeing today, as we have seen before, is that any design entrusting the enforcement of anti-discrimination laws to the political whims of presidential administrations is undeniably imperfect. Even if Texas or other states are restored to a pre-clearance system (under Section 3 of the Voting Rights Act) as a result of the voter ID and/or redistricting cases, that pre-clearance will be governed by a Sessions Department of Justice. And I would predict that the Department might have a very lax view of what policies meet the Voting Rights Act’s non-retrogression standard. This Administration has already reminded us that it is not only states and localities that can have the purpose of discriminating against minorities for political gain. The foxes are now guarding the henhouse.

The existence of private rights of action under the Voting Rights Act and other civil rights statutes is an important backstop. Public interest law firms such as CLC will continue to do this work. But the Department of Justice’s civil rights division has far greater resources to enforce these provisions nationwide. And a core function of the Department’s Civil Rights Division is supposed to be the protection of U.S. citizens from intentional discrimination.

The Department’s dismissal of its intent claim in Veasey v. Abbott is thus a clear turning away from its responsibilities in order to better support the political goals and allies of the Trump Administration. The loss of that protection will undeniably be felt in the years to come.

This blog originally appeared on the Take Care Blog.