The Rise and Fall of Mario Biaggi: Reminder of Why the Illegal Gratuities Statute Should be Revived (The Huffington Post)

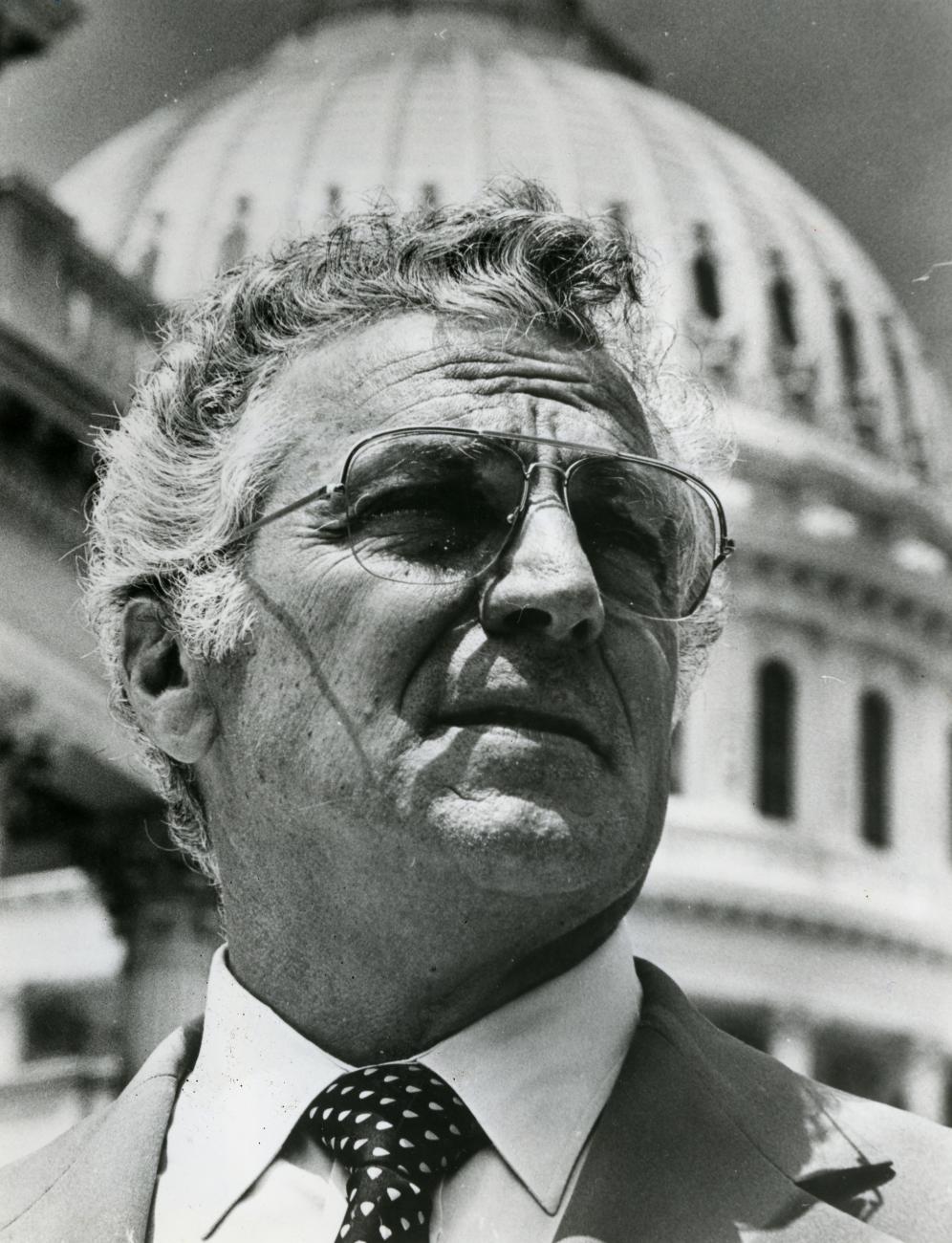

Many readers probably overlooked the recent obituary of disgraced former U.S. Rep. Mario Biaggi (D-NY). But the rise and fall of this former policeman who died at the age of 97 serves as an object lesson for aspiring politicians and makes a compelling case for resurrecting one of the most useful tools to fight political corruption--the illegal gratuities statute.

While the term "illegal gratuities" may sound like a problem for restaurant service workers, the statute was once a key tool to fight political corruption. The federal illegal gratuities statute forbids a public official from accepting something of value given for the purpose of influencing the action of that official in the discharge of his or her public duties. But after a series of court rulings, the statute was so altered that it is nearly impossible to differentiate it from the federal bribery statute, which requires making a much more difficult demonstration explicitly linking the gratuity to an official act.

A well-written illegal gratuities statute can be a key arrow in a prosecutor's quiver because it best captures the kind of currying favor that is most prevalent in politics. The passing of Rep. Biaggi should serve as a reminder about why the illegal gratuities statute is so valuable--and should be revived as a viable tool--when fighting public corruption.

Mario Biaggi had an inspiring life story. He worked as a postman and eventually rose to become one of the New York City Police Department's most decorated officers. One story had him rescuing a woman on a runaway horse, injuring himself so severely in the process that he developed a permanent limp. Another had him shooting a man who tried to attack him with an ice pick. He began law school at the age of 45 and was elected to Congress in his early 50s. Once ensconced in Congress, he prided himself on his constituent service and was re-elected by large margins.

That Biaggi would run afoul of ethics standards was not a total surprise given his rise through the rough-and-tumble of New York City machine politics. In 1987, Biaggi was indicted for accepting a free Florida vacation worth more than $3,000 from a leader of the NYC machine, Meade Esposito. Prosecutors charged that Biaggi used his influence to help a ship-repair company with federal contracts. The shipyard was a client of Esposito's insurance agency. Biaggi claimed that Esposito paid for the trips out of friendship. Shortly after the FBI interviewed Biaggi, the Congressman, unaware that his phone was bugged, called his friend Esposito to help get their stories straight. The wiretapped phone conversation between Esposito and Biaggi, introduced as evidence in court, went like this as they rehearsed their approach:

Mr. Esposito (speaking about the vacation trip): "This is not a gift. It's uh, it's a, uh, manifestation of my love for you."

Representative Biaggi: "You didn't give it to me because I'm a member, member of Congress."

Mr. Esposito: "Nah. Never, no bull. No way."

Though charged with bribery, fraud and conspiracy, Biaggi was convicted only on obstruction of justice and accepting an illegal gratuity. He was sentenced to 30 months in prison, fined $500,000 and barred from voting in the House. The next year, Biaggi was also convicted in a second case of 15 felony counts for, as The New York Times reported, "turning the Wedtech Corporation in the South Bronx into a criminal enterprise that paid bribes for no-bid military contracts. The company, a major employer in a depressed area, had been hailed by President Ronald Reagan for hiring minorities and the poor." The ambitious prosecutor in the Wedtech case was none other than future mayor of New York City Rudy Guiliani. On the verge of being expelled from the House of Representatives after being twice convicted for corruption, Rep. Biaggi resigned his seat and served a short time in confinement.

If this sounds eerily familiar it is because a similar scenario is playing out right now as Sen. Bob Menendez (D-NJ) is facing charges that a doctor, Salomon Melgen, with significant dealings with the federal government provided the Senator with free trips to desirable locations. Sen. Menendez is claiming the trips, worth tens of thousands, were given in friendship even as he interceded with the government on behalf of Dr. Melgen. The Department of Justice indicted the two this past spring.

Notably, Sen. Menendez was not charged under the illegal gratuities statute [18 U.S.C. §201(c)]. He and Melgen were charged with violations of the bribery statute [18 U.S.C. §201(b)], honest services provisions [18 U.S.C. §§1341, 1343 and 1346], and accused of a conspiracy.

Nor was former Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell charged under the illegal gratuities statute, although it probably best captures the dynamic between the McDonnells and their former sugar daddy, Jonnie Williams, Sr., who had showered them with gifts, loans, trips and other items with an eye to building his business and personal prestige through his relationship with the Governor. McDonnell and his wife also sought cover by claiming that the gifts were given out of personal friendship. McDonnell was convicted of honest services wire fraud, obstruction of justice and other corruption provisions, but notably, again, not illegal gratuities.

The reason prosecutors no longer use the illegal gratuities statute in most of their public corruption charges is that the law was eviscerated by two court rulings beginning in 1999. Before then, "illegal gratuity" meant a public official accepted something of value for the purpose of influencing the action of that official in the discharge of his or her public duties. Unlike the bribery statute, the illegal gratuities provision did not require a prosecutor to prove a specific quid pro quo, such as the wish list former Rep. Randy Cunningham wrote for his prospective defense contractor briber on a cocktail napkin.

The congressional purpose in enacting gratuity legislation was to eliminate the "tendency ... to provide conscious or unconscious preferential treatment of the donor by the donee." In United States v. Booth (1906), a federal court in Oregon said about the illegal gratuities statute:

Congress proceeded evidently in recognition of the principle that "No man can serve two masters," and that it was not right that an officer should agree to accept fees for doing services in matters where the United States is interested, before any officer of the government. The performance of duty by an officer is compensated by the salary or fees regularly allowed by law. To permit agreements for other compensation for services, to be paid by those interested in matters before government officers, would be to countenance the rendering of services oftentimes inconsistent with fidelity to the best interests of the government, to which the employee owes his first and highest obligation.

In April 1999, the Supreme Court issued a decision in the United States v. Sun-Diamond Growers adopting a narrow interpretation of the statute, holding that "in order to establish a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 201(c)(1)(A), the Government must prove a link between a thing of value conferred upon a public official and a specific 'official act' for or because of which it was given [emphasis added]." As a result, the conviction of former Clinton Administration Secretary of Agriculture Mike Espy (also a former Congressman) for accepting tickets to sporting event, meals, lodging, airfare and even luggage was overturned. Espy's lawyers claimed that the gifts were given out of friendship or a desire to establish warm feelings, so long as the items were not "for or because of official acts."

Then in 2006, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia put a stake in the heart of the illegal gratuities statute. United States v. Valdes involved a Washington, D.C. policeman who accepted money from an FBI informant as a reward for looking up license plate and warrant information on the police database for someone the informant claimed owed him money. Officer Valdes did so, accepted $50 from the informant and then on subsequent occasions, continued to look up requested information on the police database, being rewarded each time with $100 or $200. Valdes' conviction in the lower court was overturned on the basis that looking up information on the police database was not part of Officer Valdes' official duties, and thus, he had not performed a specific "official act" in exchange for money. (The Campaign Legal Center filed an amicus brief in the case supporting the conviction.)

The combination of this one-two punch in the courts not surprisingly has led prosecutors of public corruption to avoid indicting on a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 201(c). In a 2007 report, the Senate Judiciary Committee explained how the rulings affected application of the statute: "In practice, the nexus requirement means that a spectrum of cases that fall short of a bribe but plainly involve corrupt conduct may not now be charged as gratuities absent a demonstrable link between the payment and specific official action," (emphasis added). The report stated that following the Supreme Court's decision in Sun-Diamond, prosecutors rarely invoke the illegal gratuities statute because "[i]n light of the nexus requirement, prosecutors have an incentive to charge a bribe in every case that they can charge, as the burdens of proof for the two offenses are essentially the same." The Committee went on to explain:

The Sun-Diamond nexus requirement can lead to perverse results. For example, under current law, a private citizen may keep a public official on retainer by making substantial periodic payments to the official so long as there is an understanding that the money is not intended to influence any specific act, but is instead intended to build a reservoir of goodwill in the event that matters arise that would benefit the private interest. While these payments may run afoul of the gift rules, they are not actionable bribes or gratuities absent a provable "link."

Legislation has been introduced in the last several Congresses to address the issues raised by these court decisions. Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and John Cornyn (R-TX) originally introduced the "Public Corruption Prosecution Improvement Act." This rare bipartisan public corruption bill has come close to passage over the last several years, but each time has fallen short of final passage. The bill clarifies the definition of what it means for a public official to perform an "official act" to include "any act within the range of official duty" and amends the federal gratuities statute to make clear that a public official cannot accept anything of value worth more than $1,000 given to them because of their official position other than as permitted by existing rules or regulations.

The reason the measure has failed to clear the last hurdle is largely due to the Heritage Foundation, which somewhat surprisingly came out as opposed to this effort, claiming that the new definition of "official act" is too broad and would "sweep in conduct well beyond that which Congress intended." The last time the Leahy-Cornyn proposal looked like it would make it to enactment, the now-deposed Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) insisted on having the provisions stripped from the pending bill the House passed. So far, Leahy and Cornyn have not re-introduced their bill in the current Congress.

Congress' continued refusal to re-write the illegal gratuities statute means prosecutors are being deprived of one of the most useful tools to fight public corruption. Very few public officials are dense enough to write their demands on a cocktail napkin or in an email. Instead, they hide their ill intentions and even greed in the guise of friendship, fooling themselves as much as they intend to dupe the public.

Public confidence in government, especially at the federal level, is at an all time low, according to the polls. This lack of confidence has not been helped by a Supreme Court that has taken the position that just because political donors "may have influence over or access to elected officials," as Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in his Citizens United v. FEC opinion, it "does not mean that those officials are corrupt." Even more astonishing, he went on to insist that "the appearance of influence or access will not cause the electorate to lose faith in this democracy." That claim cannot be squared with reality.

Public corruption will remain with us as long as public officials wield government power. The challenge in the United States is to have, as a nation of laws, public corruption statutes that address what are totally predictable and inevitable actions when humans, in all our weaknesses and vanities, are placed in positions of power over fellow citizens. The hope is to build a political culture that dissuades many from following down this path. After all, there are too many "Banana Republics" around the world where corruption yields political systems that fail to deliver for their citizens and makes bribery commonplace at the most basic levels of government. The United States is and should remain better than this. But having no meaningful ability to use the illegal gratuities statute in public corruption cases is essentially tying one hand behind a prosecutor's back.

Rep. Biaggi's illustrative story of the heights and depth of American political life is indeed a sad one. And to the end of his days, he proclaimed his innocence, feeling he was the one who had been wronged. But his death is a good reminder of the importance of vigilance and a willingness by law enforcement to protect the public against the kinds of corruption and crony capitalism that weakens our system and erodes the public confidence essential to a vibrant democracy.

McGehee is policy director of the Campaign Legal Center and heads McGehee Strategies, a public interest consulting business. This opinion piece was originally published in The Huffington Post on July 6, 2015. To view it, click here.

Follow her on Twitter:www.twitter.com/campaignle.

Photo: The Washington Post